Services need to keep operating through shock events

Redundancy is a critical climate preparedness & resilience measure; lean stocking & staffing are no longer credible in a world where shock events are likely & becoming more frequent & widespread.

Even a less severe storm can create cascading impacts.

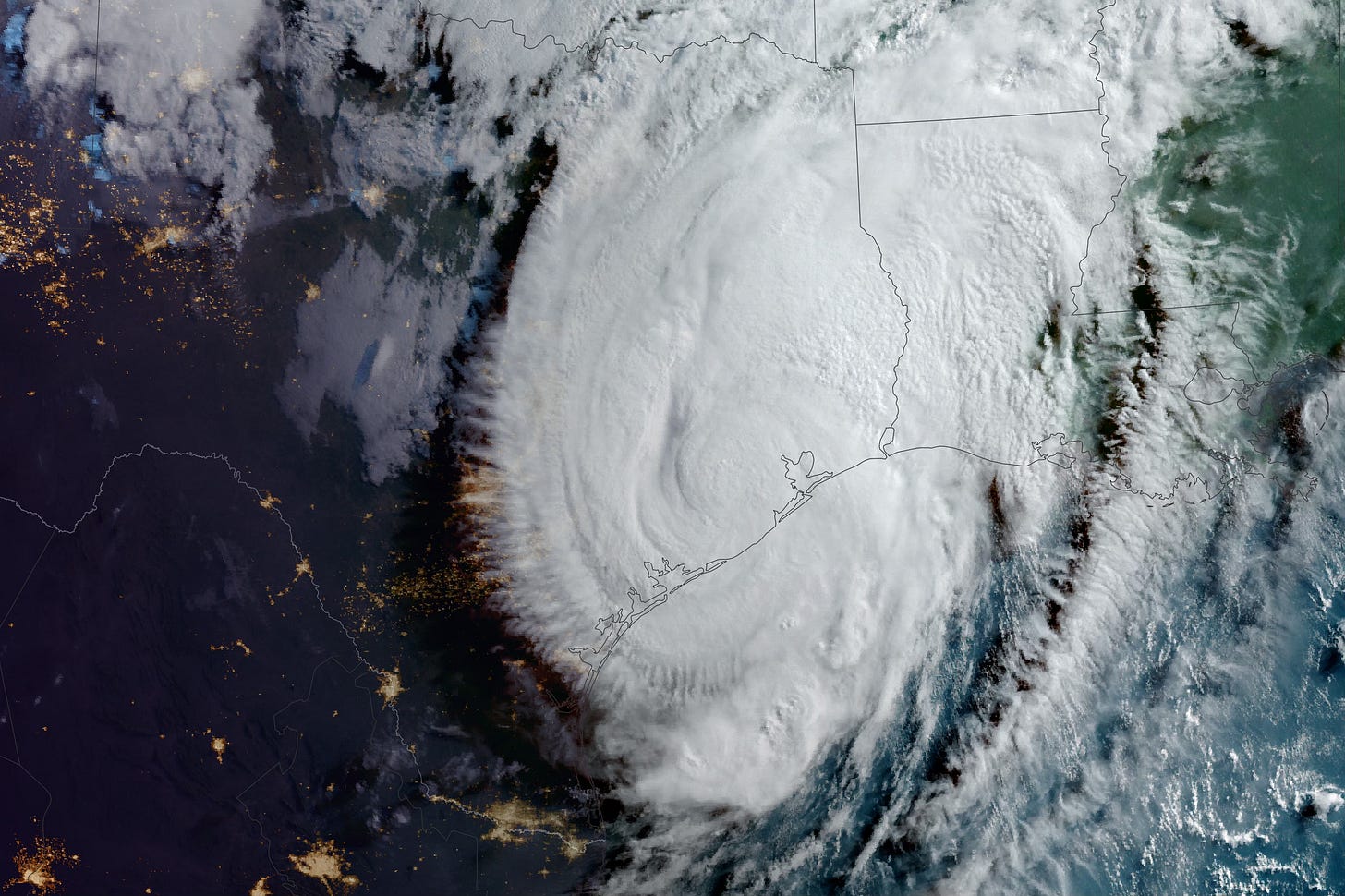

In the early morning hours of Monday, July 8, Hurricane Beryl crashed into the Houston area. Hundreds of thousands of us received tornado warnings urging we immediately seek shelter in an interior room with no windows on the lowest floor. Amid the locomotive thunder of hurricane force winds, we heard large objects crashing into our home, as accounts of storm damage and new emergency alerts buzzed on our phones.

The tornado warning was extended, while siding, roofing, and fencing materials were turned into life-threatening projectiles with jagged edges traveling at 80 miles per hour. Electricity went off and on during the tornado warnings, and about an hour into that most intense part of the storm, the power went out and stayed out.

Communications also went dark and stayed offline. There was no way to receive information verifying that the tornado warning had ended, and no way to continue tracking the storm, or to gauge how long the very real risk of sudden wind-bursts and flying debris would last. For five days, power and communications were down, and many roads remained dangerously impassable.

When the storm had eventually receded to the north and east, we were able to see that wind damage had tilted or taken apart fences and structures from various angles—the effect of hurricane-force winds winding between buildings, then catching the main current again. Siding tiles half an inch thick and a foot long had been driven fully into the ground—certainly a deadly threat to anyone in their path.

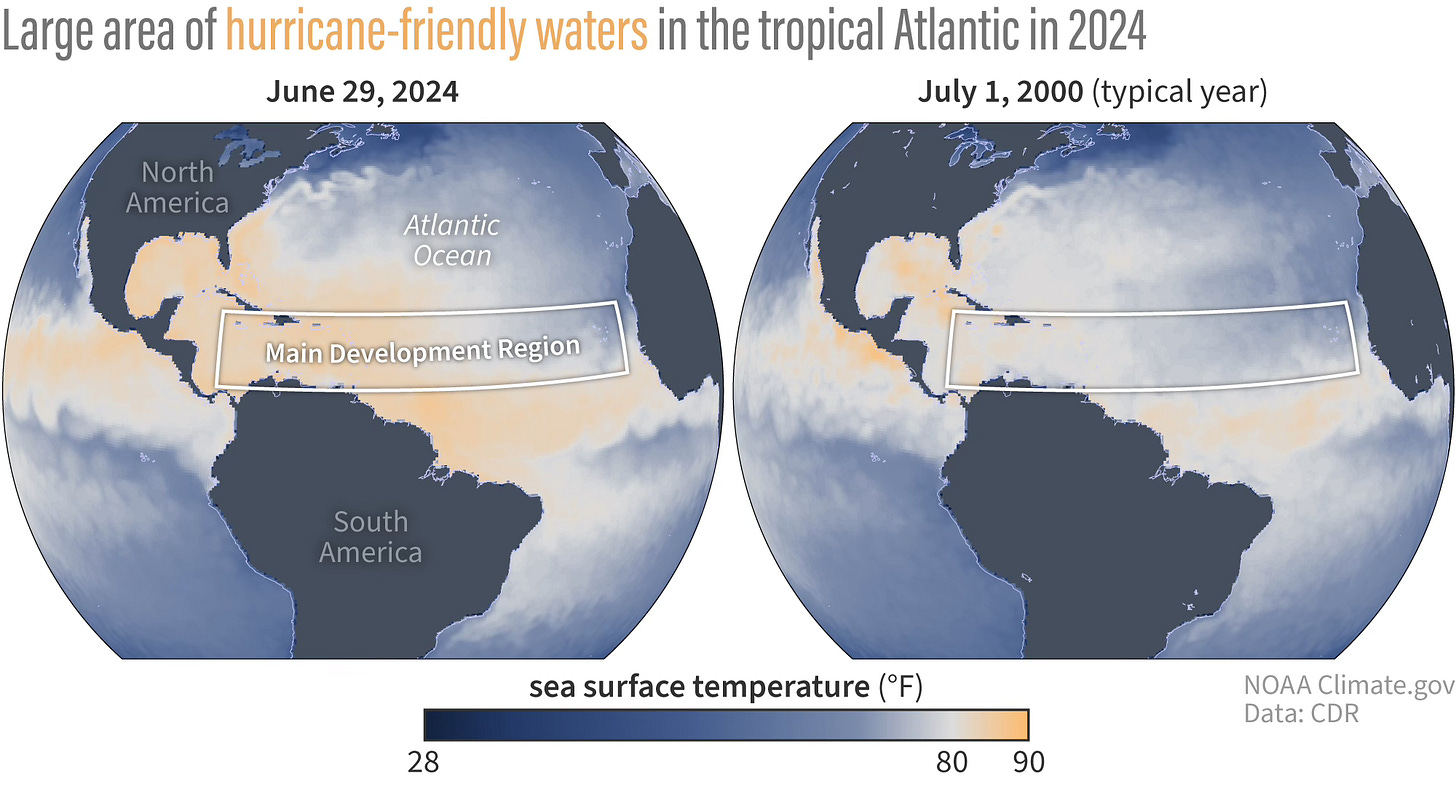

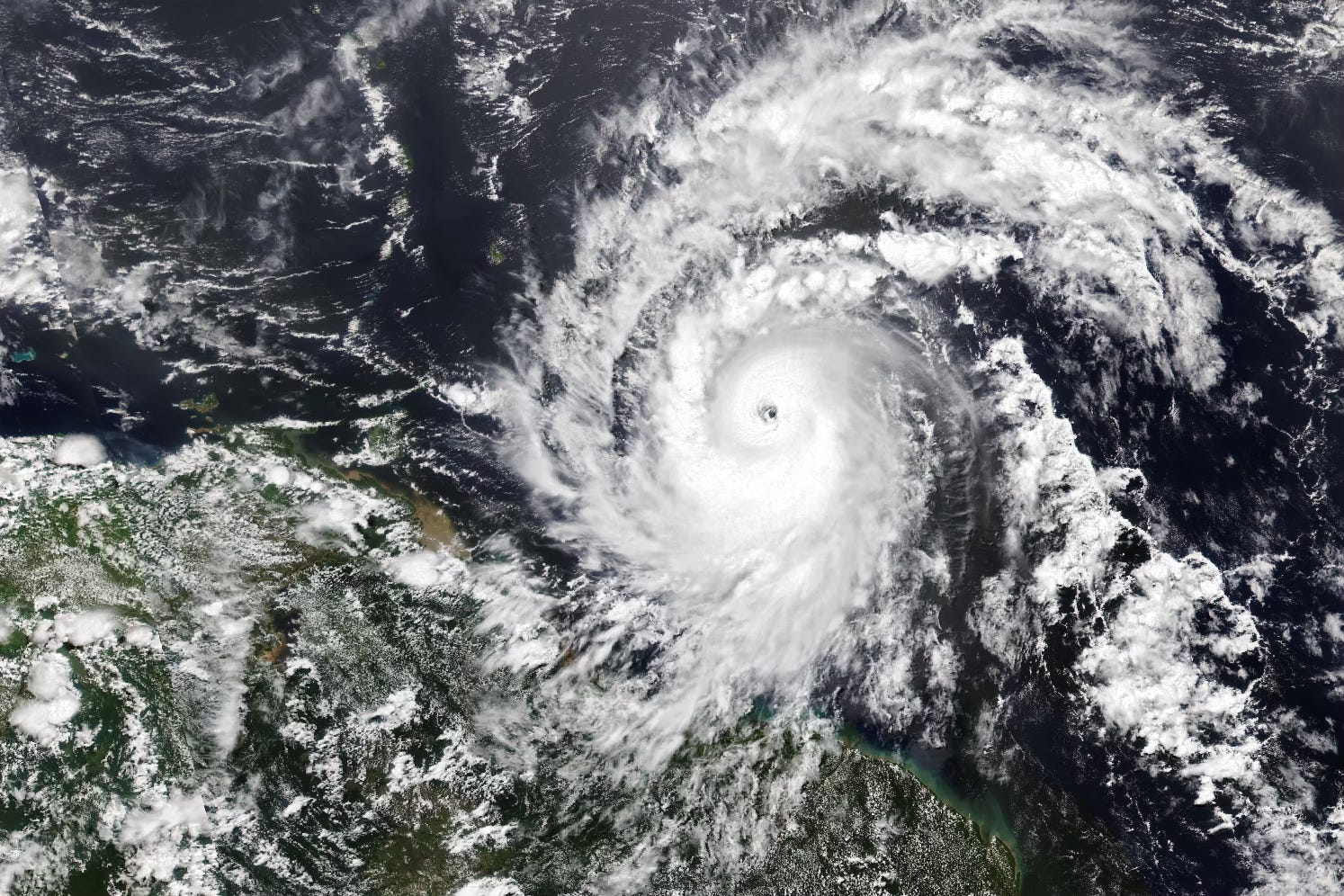

Hurricane Beryl was a Category 1 storm when it arrived in Texas, as rated by windspeed. It was a record-breaking Category 4 hurricane when it made landfall in Carriacou, St. Lucia, Grenada, and other islands across the Southeast Caribbean. Record ocean heat drove Beryl from a tropical depression to a major hurricane in just 42 hours, two months earlier than the other 5 storms that grew, organized, and stregnthened that quickly.

Beryl would reach Category 5 after impacting the first islands it struck, strenghtening as it crossed the historically warm Caribbean Sea. That repeated rapid acceleration is part of what allowed Beryl to not only reach the Yucatan Peninsula and Texas, but to hit them with dangerous extreme weather and then to carry on for thousands of miles to the north and east.

Redundancy is security.

Because communications were still down, people began to venture out in search of high ground, in hopes of getting access to wireless internet and phone signals from outside the affected area. Elevated bridges over railways had cars backed up on the roadside trying to get a signal and get word out about conditions and needs, and whether they had come through alright.

During the coming week of power outages and ongoing physical danger, the Mayor of Houston would raise alarms about disaster preparedness, noting that—due to conflicting surgical and emergency commitments—only 4% of the city’s ambulance fleet was available for new emergencies at one point. Millions of people became acutely aware of their vulnerability, once it became clear that:

Communications were down and not coming back, along with the power supply;

Emergency services might be hard to reach, or understaffed and undersupplied;

Healthcare facilities were having backup generators brought in that were not already in place;

Pharmacies and other essential local businesses were shut down, due to the power outage, with no secondary power sources and no emergency assistance from local or state authorities;

Roads were impassable, and crews had not yet been contracted to clear them.

Not enough redundancy was built into the system, so neither power nor communications came back up quickly. Laissez-faire policy had left businesses relevant to disaster response, like major telecom companies, underinvesting in redundancy and not able to quickly get power and repairs to damaged towers.

If a tornado warning coincides with a power outage, and there is no further updated information that those seeking shelter can access, how can people know conditions have changed? Those without information can be misled by their immediate environment to believe they are safe to move around in open air.

If a greater danger than previously suspected now sits 24 hours out, and late evacuation is both possible and strongly advised, but power and communications are out… how can people receive the information they need? Why was there apparently no secondary layer of emergency wireless phone service to push warnings and updates to residents?

These are life and death questions. The answers to these questions need to be practical interventions in the physical world, made well in advance of any disaster. Leaving these questions unanswered until after a shock event occurs condemns an unknown number of innocent people to serious risk of injury and potential loss of life.

Early warning is just the beginning.

The United States has world-leading early warning systems. Part of this is the result of an open culture of nonstop debate. Because we are always talking, communicating, comparing notes, and criticizing the shortcomings of the status quo, we have a tendency to embrace wave after wave of innovation, to solve problems large and small. But open debate is not enough.

In the event of extreme weather, such as hurricanes, American citizens and towns often have a week or more advance warning; updates are given frequently, and end with a note about the projected timing of the next update. The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Weather Service (NWS) are foundational for allowing this level of early warning. They literally change the game, and make it possible for all of society to prepare for emergencies and materially reduce threats to human life.

There are two major vulnerabilities that affect even the best-case detailed, always-on early warning systems:

one is that vulnerable communities are often the least able to access and mobilize resources around such information;

the other is that once a shock event starts, communications might not be available.

Early warning systems must be extended by always-active communications through a disaster, with remote and local information-sharing persisting into the aftermath and disaster response. Early warning and disaster response systems need hard infrastructure, including multiple layers of redundancy, to maintain access to wireless internet-based communications.

Disaster response plans need upgrading everywhere.

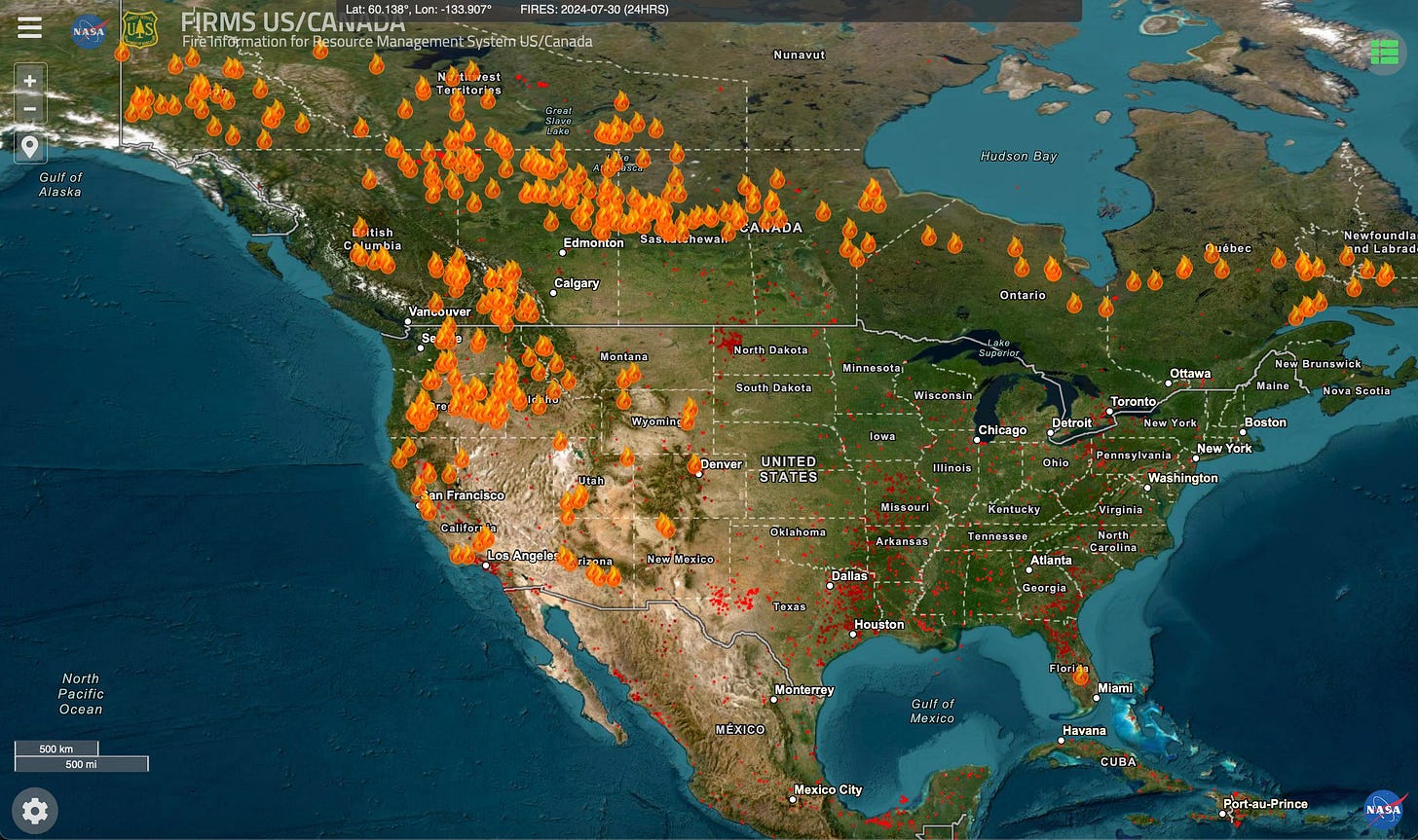

At this writing, massive wildfires fueled by global heating are burning across the planet. In Canada, which lost an area of Boreal Forest last year equal to the total combined area of half the nations on Earth, the historic Rocky Mountain city of Jasper, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was destroyed by fire. In California, some of the largest fires in history are ravaging multiple counties, forcing desperate last-minute evacuations and retraumatizing towns like Paradise, which was already totally destroyed by the state’s largest ever fire.

Wildfires are now more frequently becoming firestorms. A firestorm is a wildfire so large it creates its own weather systems—including pyro-cumulus storm clouds that can rise to 45,000 feet, piercing the stratosphere. Such fire-induced storm clouds produce lightning which can spread the fire miles beyond the firefront. Municipalities large and small now need to be prepared not only for fire, but for the sudden-onset danger posed by firestorms that could emerge anywhere in the surrounding region. Evacuation routes may also need to be redesigned, which may include re-engineering of roads and bridges.

In the last two months alone, historic floods have devastated India, Nigeria, Arizona, and many other places.

Hurricane Beryl traveled 6,000 miles from Africa to Texas and then northeast across the United States and as far as Atlantic Canada, bringing floods everywhere it traveled.

Northern India’s floods have resulted from glacial lake outbreaks, repeated cloudburst rain events, and failure of hydroelectric infrastructure to fit the worsening pressures of a climate-altered world. In the southern state of Kerala, heavy rains caused devastating floods and took the lives of at least 123 people.

India, Nigeria, and other nations are seeing shock flood events destroying crops and undermining the security of local and shared food supplies.

An increasing number of regions are finding themselves facing shocks from drought, fire, storms, and floods, sometimes simultaneously. Food systems are increasingly insecure at the regional and global levels.

In the age of record global temperatures and worsening climate disruption, service providers, public agencies, and markets need to align incentives and financial opportunity with that better standard of preparedness and response. It is simply no longer a credible business strategy—when lives are on the line—to claim that lean contingency planning is “efficient”.

Early warning systems are crucial; they need to provide real-time updates, advanced warnings and ongoing guidance, to affected communities, and to relevant businesses, agencies, and institutions. The communications infrastructure through which warnings and disaster response guidance are delivered must also hold up and be easily brought back online in the midst of shock events.

This is a design question, a policy question, and also a question of business strategy. Those commercial enterprises, large and small, that figure out the right way to meet this need will be favored by emerging market conditions, as climate-related shocks become more frequent and more intense. People and public agencies will reward such enterprises, because lives may depend on their success.

For more about efforts to reduce risk and build resilience as mainstream economic activities, visit the Climate Value Exchange.