Our Collective Moment of Crisis

Climate, COVID, conflict & a background of worsening inequality, are putting lives, nation states & Nature itself at risk. We can create a sustainable future, if we take the right steps, right now.

Our interconnected world is grappling with interconnected crises that magnify and compound each other’s effects. We have long known that climate disruption was going to create ripple effects, but now we are living through those ripple effects while other forces create emergency-level immediate challenges.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has triggered a global food security crisis, which will only deepen if food exports do not start moving. This was foreseeable, and it was foreseen. Putin’s criminal war was not only a choice to abandon the United Nations Charter and commit war crimes. It was a clear and knowing choice to create a global food crisis in which hundreds of millions of innocent people will suffer.

This food supply crisis is not triggered only by the war, however. Sharp price increases—resulting from pandemic-related supply-chain disruptions, diverted and distorted capital flows, and reduced yields caused by climate impacts—have been made worse by reduced purchasing power in much of the world, especially in the least developed countries, also resulting from the pandemic.

All of this has made it harder for most people in most of the world to find sufficient amounts of affordable food.

Sharp price increases across the economy—what central banks call “inflationary pressures”—have also been triggered by coordinated fossil fuel supply cuts designed to push prices up. Add this coordinated fuel supply cut, and corresponding price rises, to the other factors listed above, and we find ourselves with what The Economist describes as a looming “food catastrophe”, in which “hundreds of millions more people could fall into poverty. Political unrest will spread, children will be stunted and people will starve...”

A similarly stark headline in Politico paraphrased the warning from David Beasley—the head of the World Food Programme—with the words “Get ready for ‘hell’…” Beasley warned that failure to provide funding and get food shipments where they need to be, quickly, would result in “famine, destabilization and mass migration” across multiple regions.

The food crisis is also connected to the fact that Ukraine is such a major contributor to world grain exports and food aid, in particular. The World Bank reports:

“Russia and Ukraine are two of the world’s major grain baskets. Together they provide some 25% the world’s cereals. Nearly 50 countries depend on Russia and Ukraine for at least 30% of their wheat import and, of these, 36 countries source over 50% of their wheat from the two countries.”

These pressures are building, quickly. The Economist article cited above notes:

“Since the war started, 23 countries from Kazakhstan to Kuwait have declared severe restrictions on food exports that cover 10% of globally traded calories. More than one-fifth of all fertiliser exports are restricted. If trade stops, famine will ensue.“

All of this comes on top of the still ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which has:

Pushed hundreds of millions of people into poverty;

Greatly stressed and disrupted regional and global supply chains;

Increased vulnerability of communities and institutions;

Cost the US alone at least $16 trillion so far;

Caused an estimated 15 million deaths, globally, so far.

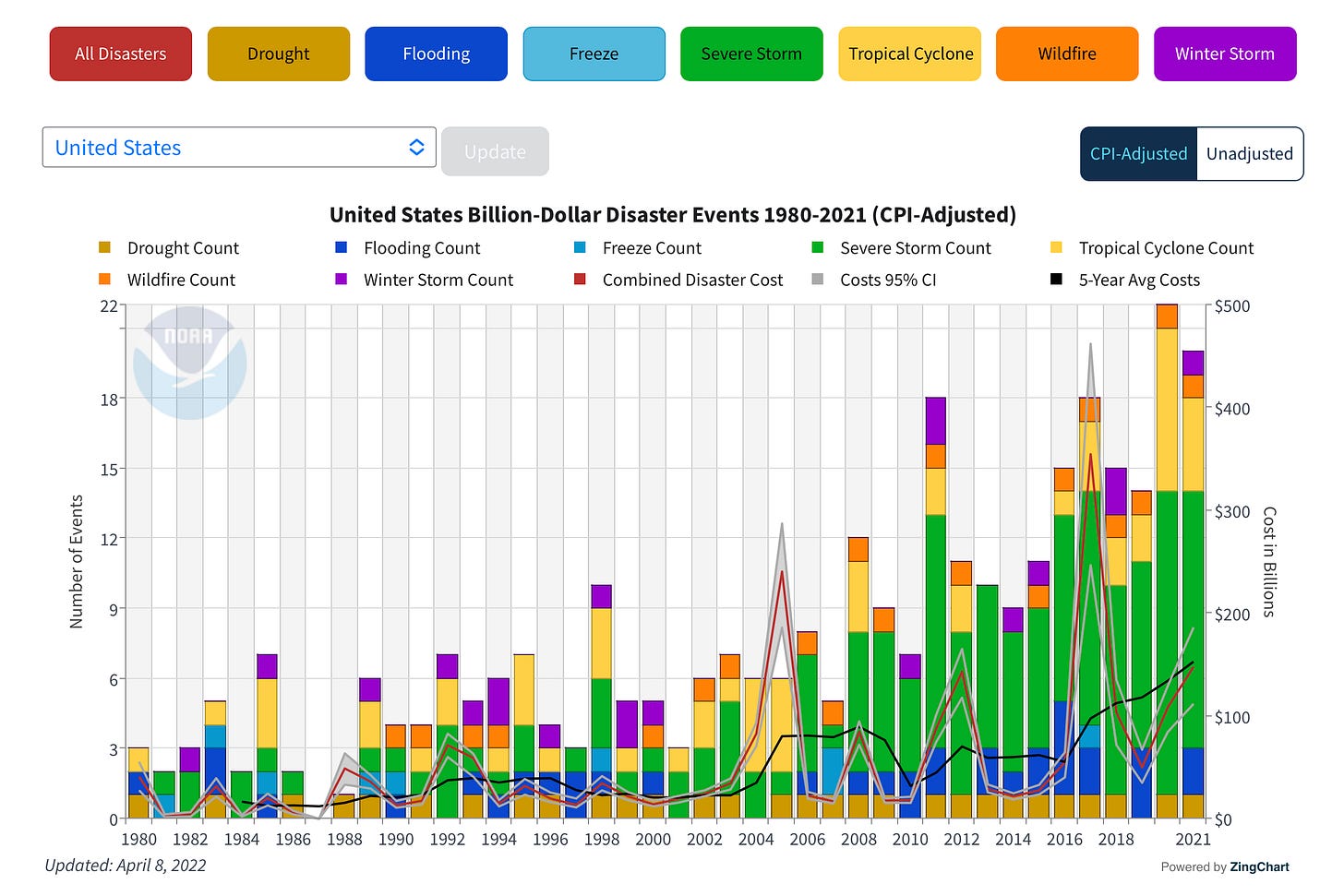

And, the climate crisis is deepening. It is becoming harder to produce food, as watersheds, ecosystems, biodiversity, and soils, are all depleted, and as global heating and climate disruption make rainfall and other natural life supports less reliable. Meanwhile, the cost of responding to climate-related disasters is quickly accelerating, putting additional downward pressure on incentives that can help to build resilience and drive adoption of sustainable practices.

These impacts reduce both earnings and savings for farmers, and lead to a faster pace of land conversion—expanding industrial production, monocropping, ecosystem degradation, chemical inputs, cost of chemical inputs to small farmers, and driving a shift to industrial outputs, like materials and combustible fuels. These are feedback engines, creating spirals of impact that make it harder to reduce risk.

A United Nations’ global report on Disaster Risk Reduction found that the world will be facing 1.5 major disaster events per day, by 2030.

50 years ago, in Stockholm, the world came together to recognize that ongoing environmental degradation would create unmanageable long-term risks. The result was a commitment to environmental protection and sustainable development. In 1992, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) united the world in a commitment to prevent dangerous human-caused interference with Earth’s climate system.

Nature loss, and the rapidly intensifying global biodiversity crisis are part of this vicious cycle of degradation and declining security. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services reports:

“The global rate of species extinction is already at least tens to hundreds of times higher than the average rate over the past 10 million years and is accelerating.”

1 million species are estimated to be at high risk of extinction. This makes it harder for pollinator species to survive, thrive, and adapt, and that makes it harder for agricultural lands to achieve ecological resilience and reliably produce food through changing climatic conditions.

We have long known we will need to act sooner, rather than later, to avoid catastrophic negative consequences later on. Now, for the first time, we face the most stark version of that challenge:

We must address immediate, short-term emergencies in food and energy security, while transforming financial systems and managing the impact of armed conflict, present-day climate change, and an ongoing pandemic.

AND, if we don’t succeed in doing that in a way that fosters real sustainable conditions for human development later on, we will lock in all of these crises as ongoing threats to human security.

The Global Crisis Response Group on Food, Energy, and Finance, convened by the United Nations Secretary-General, is the first-ever human endeavor to face this dual challenge in real time, with existential long-term consequences. This is the moment—more than any other we have faced—when we will choose either a future that can work for all people, or one that works for almost no one.

Sustainable investment is often labeled “ESG”, which stands for Environment, Social, and Governance—referring to three broad categories of metrics designed to track a company’s performance in ”non-financial” areas of impact.

Environment and social refer to “positive externalities”—the wider non-financial benefits an investment decision contributes to everyone else.

Governance refers to the integrity of an investment, or a business model and to the complicated question of how we know it has that integrity.

ESG recognizes that transparency, accountability, and external value creation, beyond profits, are all key to assessing the value of a decision.

We need data systems to be inter-operable and mutually informative, so financial decision-making is able to actively consider Earth systems insights, wider socio-economic dynamics, including public health considerations, that shape the overall value potential of an economy, and condition each decision within it. And, we need ways for stakeholders to actively participate in decisions that will affect their current and future living conditions and prospects for sustainable thriving.

And yet, participatory processes and open societies are being eroded across the world. When we need to come together in solidarity, to address a multidimensional moment of crisis that affects everyone on Earth, unaccountable use of power appears to be taking more ground. Or at least it was, until recently.

The invasion of Ukraine might be a breaking point. Even other violent autocrats appear worried by the apparent madness of Putin’s criminal endeavor, and by how difficult it turns out to be to win an actual war. Democratic nations have banded together and enforced an unprecedented sanctions regime on a former major world power. It may now take generations for Russia to return to that status.

We must treat every aspect of this moment as gravely consequential:

We cannot afford to make future climate change worse in order to get an easy fix now on energy prices.

Doing so would virtually guarantee severe and possibly irreversible food security stress in one or more regions around the world.

We also cannot afford for this moment of interconnected crisis to result in a global turning away, where multilateral cooperation is greatly reduced.

We need more imaginative, more robust, more reciprocal multilateral cooperation, to build resilience against major shocks.

We also need greater solidarity between people of diverse nations, to honor and expand basic human rights protections.

Our collective moment of crisis reveals connections between today’s decision-making and tomorrow’s prospects for security and prosperity. It also makes sustainability-oriented innovation and best practices into immense opportunities for building a better future and conditions of security and prosperity which can benefit everyone.

Additional Resources

SCIENCE REPORTS

Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change – IPCC Working Group III

Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate – IPCC

FOOD, ENERGY & FINANCE