Digital Climate-informed Advisory Services key to food security & future prosperity

One of the central principles of the work we do at on science and innovation Geoversiv, on climate and civics at Citizens’ Climate International, and on food systems at EAT, is the recognition that human thriving is not possible without healthy natural systems.

We need to know the state of our relationship to natural systems that sustain life.

What we sometimes lose in the debate between “business as usual” and “a sustainable future” is that “unsustainable” equates to “accumulating hidden costs”. As those costs pile up, the health of our relationship to live-giving systems is degraded. When natural systems are degraded, or worse, when our activities drive the degradation of natural systems, we undermine our own future chances at wellbeing.

Small steps forward or backward create a complex evolutionary picture, which is partly drawn by data, and partly by experience of narrowing safety corridors, shock events, spreading instability, and scarcity. What we don’t know can hurt us; not knowing enough about the health of natural systems can make our most cherished aspirations impossible to achieve.

Take the basic question of food production and food prices. For several decades, we have been expanding, integrating, and hardening a global economic framework that treats food security as an over-simplified formula: more food, produced more cheaply, keeps prices lower; integrating production to create industrial economies of scale consolidates this effect; so… industrial food production keeps food cheap.

Food prices are driven by supply and demand (more supply = lower prices; more demand = upward price pressure). It is well understood that a price increase of just 1% above inflation can cause serious socio-economic and political instability in much of the world. The US often manages with more significant price fluctuations, but the ripple effects are only dampened by major public assistance.

None of this accounts for the impact of a particular production method, incentive structure, or market effect, on the health of natural systems. Historically, we had a safety net, in the sense that we hadn’t yet disrupted planetary systems, like the climate, to the point where ecological degradations driven by industry would make reliable food production impossible.

We are now getting there. “Earth Overshoot Day”, as Jeremy Coller, Johan Rockström, and Gunhild A. Stordalen noted in an article in July, “is the date in the year when the annual capacity of our planet to regenerate what we take from it is used up”. That date is earlier each year, as we are overconsuming Earth’s resources and depleting vital natural capital, year after year.

Hundreds of millions of food producers have little or no access to reliable data about the natural systems that make their livelihood possible.

This knowledge deficit is a threat to human health and wellbeing. It could be one of the critical forces in a complex process of food system failure. Climate science observations and projections suggest we will experience “simultaneous breadbasket failure” sometime in the next two decades.

That’s something worse than harvest failure in more than one region at a time; it means the functional failure of multiple major food-growing regions, which would have a devastating impact on the global food supply. We need to deploy far better systems impact information, and reimagine food production, distribution, and consumption, as part of the global effort to prevent a catastrophic shock.

Digital climate-informed advisory services have the potential to not only help farmers make better choices about how to manage the natural capital they depend on, but to provide the data necessary to mobilize government incentives and flows of new investment aligned with climate-smart, Nature-positive food systems.

According to the World Resources Institute:

The Global Commission on Adaptation paper, A Blueprint for Digital Climate-informed Advisory Services, finds that expanding the reach and quality of these digital services will require governments and the private sector to invest approximately $7 billion over the next decade. Given that approximately $1 billion has been invested in DCAS in the last five years, this means an exponential push in collective investment from both public and private sector actors is needed in the years to come.

The return on investment will be staggering. As financial regulators move to require detailed climate risk disclosures, and governments shift to incentives conditioned on natural capital impacts (on fresh water, soil biomass, or forests, for instance), the total value of risk reduction alone will far exceed the projected $700 million/year investment in DCAS.

The COVID pandemic has shown us the cost of knowledge deficits in resilience-related planning. Major industries were not prepared for a global economic shock from a single zoonotic virus spillover. Some struggled to adapt even a single operational detail, such as location of delivery.

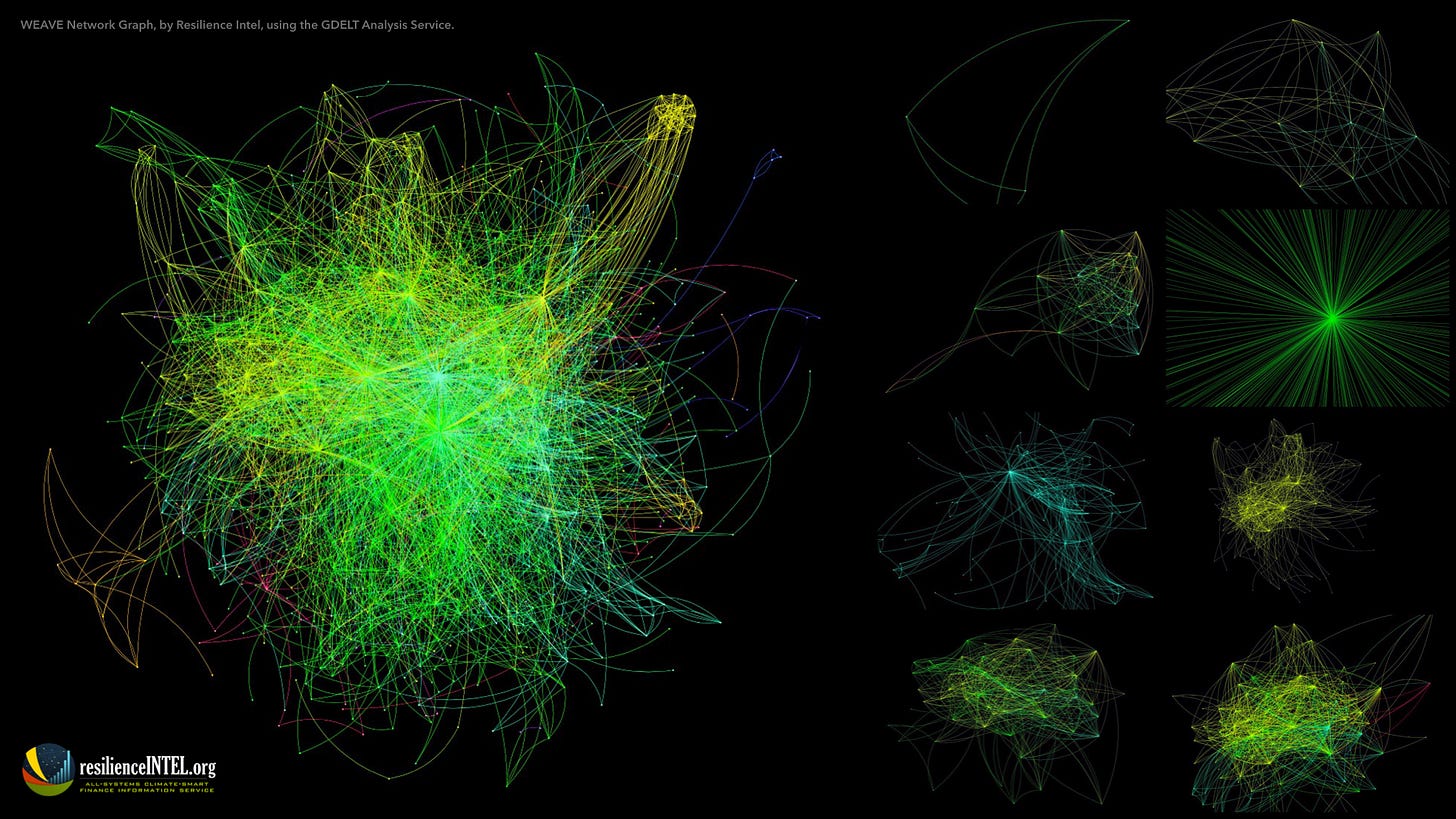

A convergence of resilience deficits—pervasive diet-related non-communicable diseases, sub-optimal financial sector regulatory requirements, subsidies not aligned with preparedness for systemic shock events—made the pandemic emergency far more costly in lives and treasure than it needed to be. We need the neural map of our resilience knowledge to be far more robust, detailed, and adaptive.

To get there, we are going to need to:

network Earth systems data to financial and socio-economic data;

require recipients of major public support—including agricultural, financial interests, and major industrial operations—to align with climate-smart resilience-building priorities and practices;

de-risk investments that support these better practices;

reward food producers and other industries for benefits they produce for the health and resilience of natural systems;

and make digital climate-informed advisory services a user-friendly, value-building part of our everyday economy.

We can escape out-of-control planetary emergency, but only if we act immediately, at the highest level of ambition, with the best use of information, everywhere, in a sustained way. That is what the science is now telling us. We need to look for, and ask for, creative ways to make Earth systems information part of our lives.