Climate emergency is a threat to international peace & security

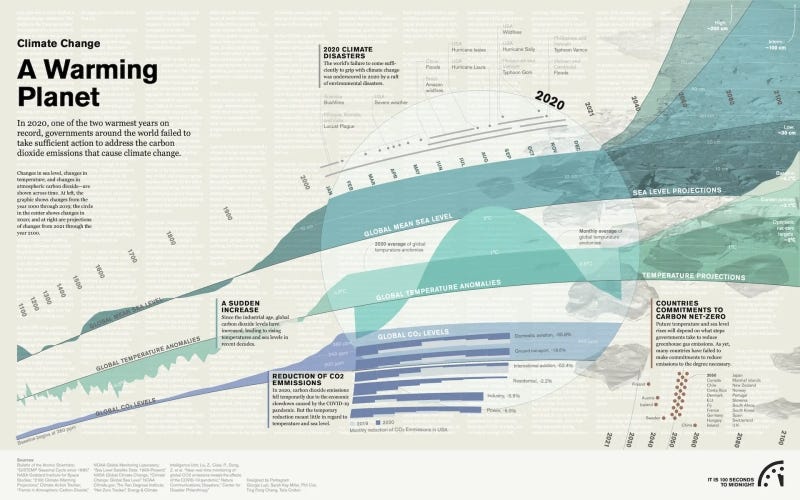

In January 2021, the Science and Security Board of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists warned the “Doomsday clock” was at “100 seconds to midnight”. The COVID-19 pandemic has destabilized economies and nation states, compounding risk factors that could lead to nuclear conflict. The authors, including 13 Nobel Laureates, warned that:

wanton disregard for science and the large-scale embrace of conspiratorial nonsense—often driven by political figures and partisan media—undermined the ability of responsible national and global leaders to protect the security of their citizens.

The resulting trauma, “social chaos” and breakdown in trust make it harder for all nations to confront major challenges. The statement noted the grave threat posed by worsening climate disruption. During global climate talks in Glasgow in November, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson told world leaders the clock now stands at “one minute to midnight”.

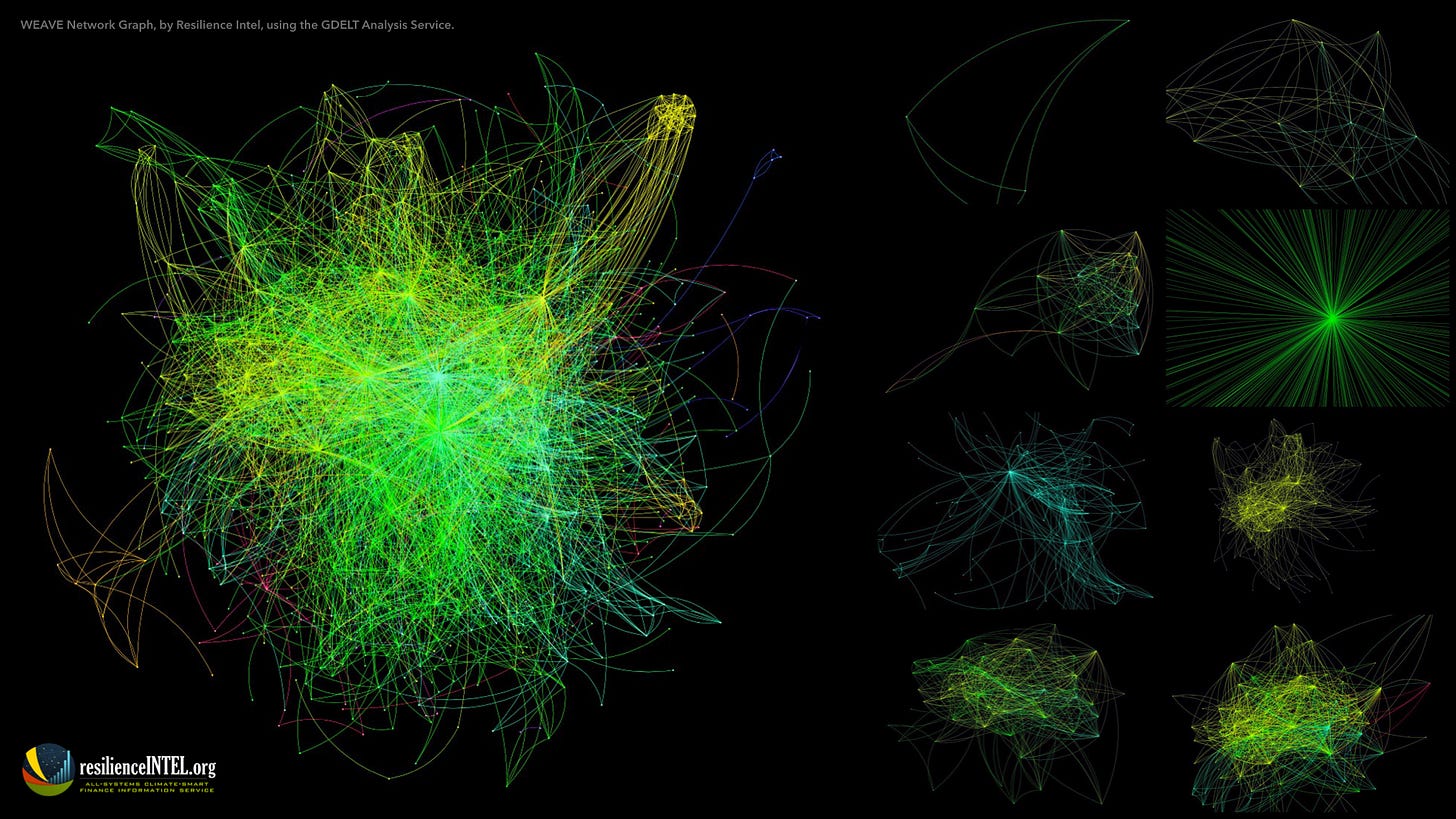

Worsening disruption of Earth's climate system is a threat to international peace and security. A 2009 report (A/64/350) requested by the United Nations Security Council highlighted climate change as a “threat multiplier… that can work through several channels… to exacerbate existing sources of conflict and insecurity.”

The report also cited 5 general areas of threat minimization that should be undertaken to reduce climate-related conflict risk:

effective international and national mitigation actions, supported by finance and technology flows from developed to developing countries;

strong support to adaptation and related capacity-building in developing countries;

inclusive economic growth and sustainable development, which will be critical to building resilience and adaptive capacity;

effective governance mechanisms and institutions;

timely information for decision-making and risk management.

According to the 2009 “threat multiplier” report to the UN Security Council:

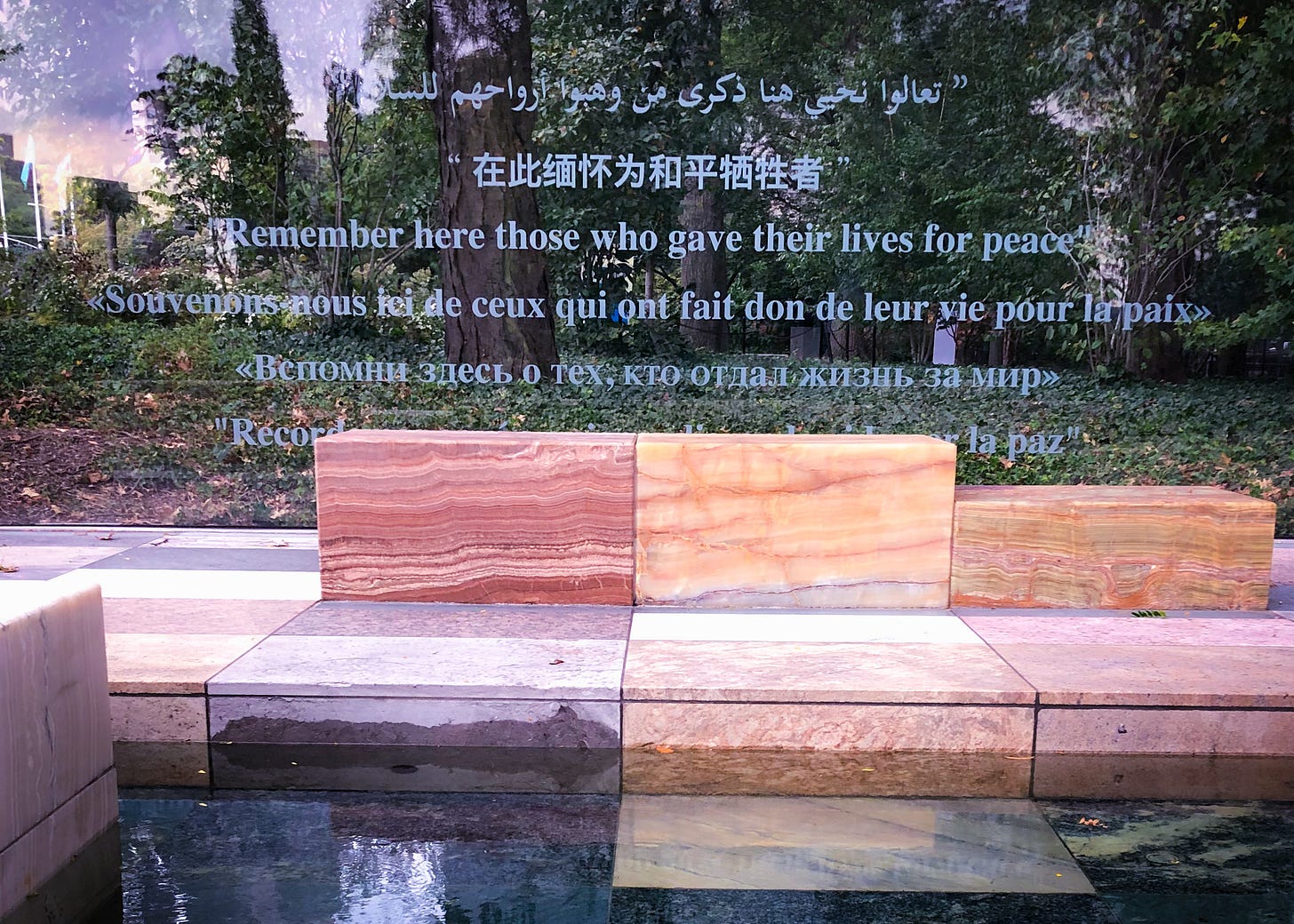

International cooperation will also need to be reinforced to address transboundary effects and to prevent and resolve climate-related conflicts in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.

Conflict prevention in the 21st century requires concrete action to mitigate climate-related risks and impacts.

Already, tens of millions of people are displaced, either internally or internationally, as a result of extreme events, including sustained severe drought conditions, failing watersheds and ecosystems, and vulnerability to shock events along coastlines and in mountainside landscapes.

As notes from Security Council debate observe, more than 50 million are living in precarity in the Sahel region alone.

In the next 2 to 3 decades, the scale of forced migration due to climate impacts is expected to eclipse even the worst moments history has seen.

More than one nation will likely run out of water as climate breakdown deepens, while food price shocks, the incidence of spillover viruses like SARS-CoV-2 (which causes COVID-19 disease), and other threats to human health and economic stability, are getting worse.

Unchecked climate change increases the likelihood of "multiple breadbasket failure", meaning the simultaneous collapse of harvests in multiple major food-growing regions, resulting in extreme global food supply shortages.

All of this must be considered in the context of the August 2021 contribution of IPCC Working Group 1 to the 6th Assessment Report, which looked at 5 possible climate futures. The report found that only in the most ambitious scenario, involving maximally effective and persistent climate action everywhere, starting now, will we be able to limit global heating to 1.5C or lower.

For financial holdings to continue to hold value as intended, and for that value to reliably expand over time, all investment decisions need to become climate-smart and climate-safe. That means national policy needs to steer whole economies away from climate-destabilizing pollution.

The decision by Vladimir Putin to order a veto of the United Nations Security Council resolution recognizing climate change as a security threat is dangerous and ill-conceived. Slowing climate action and related conflict prevention will harm the Russian people in several ways:

It will make the climate emergency Russians face more extreme and more expensive.

Russia's ongoing commitment to profit from a dangerous and dying business model will eventually bankrupt its economy.

Refusing to work with other nations to reduce the risk means rescue funding will come to Russia last or near last.

This will accelerate the collapse of Russia's economy, food system, and institutions.

The threat of deep instability in Russia is not only a threat to the Russian people. It is a threat to global peace and security, because of:

Russia's expansive territory;

the devastating challenge of maintaining infrastructure on thawing permafrost (which makes up 60% of Russia’s territory);

accelerating risk of mass migration in both directions across Russia's borders,

the potential for regional and ethnic conflict;

a massive arsenal of nuclear and chemical weapons;

a close affiliation of official institutions with organized crime.

All of the conflict risk drivers facing Russia will become materially more immediate, more severe, harder to manage, and more expensive, if climate change is not halted. This is also true for India, which joined Russia in voting against the Security Council resolution. Compounding climate impacts undermine everyday resilience, and delaying action makes it harder to deal with shocks when they come.

Russia's unaccountable regime is chasing a fantasy that somehow it will force not only the world community and with it public, private, and multilateral finance, but also Nature, to go along with their scheme. In that fantasy, Russia will continue to use oil and gas to extract concessions and wealth from people who have far better futures available to them, even as all of the above threats worsen, and Russia itself is destabilized.

Any government working to secure a better future for its people already recognizes that climate change is a threat to peace and security, and to the stability of nations. This resolution should be reintroduced, with increasing detail, even as responsible nations continue to work to end the threat of unchecked pollution-driven climate emergency.

Additional Resources

For more information on climate-related security risks and United Nations Security Council action, read “Climate Security at the UNSC - A Short History” by the Climate Security Expert Network.

Citizens’ Climate International reported here on UNSC deliberations on climate and security earlier this year.

The Earth Day Climate Communiqué, an outcome of the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize Forum in Oslo, Norway, covering climate change security risk and pathways to climate security.

The presentation “Restoring Cooperation in a Fractured World” reviews civic, economic, financial, and geopolitical means of building security through cooperative climate action.

“Reinvent Prosperity, Include Everyone, Secure the Future”—a progress report for global efforts to recover inclusively and sustainably from the COVID crisis.

The Geoversiv statement of support for a call to action on Planetary Emergency and its proliferating risks.